Establishing the need for $\sigma$-algebras

Unintitively, establishing a sense of magnitude or measure on subsets of the real numbers requires work. You would expect a function $\mu$ that measures the reals to have the following properties:

- $\mu$ can measure all subsets of $\mathbb{R}$. That is: (Note: $\infty$ is needed to denote ‘infinite size’)

$$\mu: \mathcal{P}(\mathbb{R}) \to [0,\infty]$$

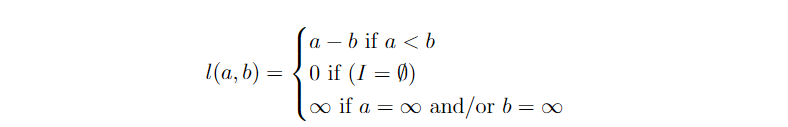

- $\mu$ generalizes natural notions of length. That is, for some open interval $I = (a,b)$:

$$\mu(I) = l(a,b)$$

Where,

It is easy to prove that $\mu([a,b]) = l(a,b)$.

- $\mu$ is translation invariant. That is $\forall A \subseteq \mathbb{R} \text{ } \forall t \in \mathbb{R}$ and $+$ is element wise addition:

$$\mu(A+t) = \mu(A)$$

- $\mu$ is countably additive. That is for some disjoint sequence of sets $A_i$:

$$\mu\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty}A_i\right) = \sum_{i=1}^{\infty}\mu\left(A_i\right)$$

- $\mu$ preserves order. That is, $\forall A,B \subseteq \mathbb{R}$

$$A \subseteq B \Rightarrow \mu(A) \le \mu(B)$$

Now we will show that such $\mu$ does not exist. The below proof of this invokes the axiom of choice: for any non-empty set of sets $A$ a new set consisting of exactly one element of each set $\in A$ can be created. This axiom of set theory is a controversial one, most especially in its use as below (choosing from a set of uncountably many sets)

Proof: No such $\mu$ exists

Consider the unit interval $I = [1,0]$. Consider the relation $R$ on $I$ defined as:

$$aRb \Leftrightarrow a-b \in \mathbb{Q}$$

Clearly this is an equivalence relation:

-

$R$ is reflexive ($aRa$) as $\forall a \in [0,1] \text{ } a-a = 0 \in \mathbb{Q}$

-

$R$ is symmetric ($aRb \Rightarrow bRa$) as $\forall a,b \in [0,1]$, if $a-b \in \mathbb{Q}$, then $-(a-b) \in \mathbb{Q}$ and therefore $bRa$

-

$R$ is transitive ($aRb \land bRc \Rightarrow aRc$) as $\forall a,b,c \in [0,1]$ if $a-b \in \mathbb{Q}$ and $b-c \in \mathbb{Q}$, by the closure of addition $(a-b)+(b-c) \in \mathbb{Q}$ and hence $aRc$

By the nature of equivalence relations, $R$ partitions $I$ into equivalence classes. Clearly, all the rationals in $[0,1]$ fall in the same class. The other equivalence classes would be of the form:

$$[p] = \lbrace p+q \text{ }|\text{ } q \in \mathbb{Q},\text{ } p+q \in [0,1]\rbrace$$

for every irrational number $p \in [0,1]$. Clearly there are uncountably infinite equivalence classes (irrationals are dense in the reals), each having countably many elements (the rationals are countable).

Now construct a set $V$, called the Vitali set, containing exactly one element from each of the equivalence classes. In doing so we have invoked the axiom of choice.

Consider an enumeration $e_i$ of all the rational numbers in the interval $[-1,1]$. Consider the sequence:

$$V_i = V+e_i$$

Where $+$ is element wise addition. Note that, $\forall i \in \mathbb{N}$,

$$V_i \subseteq [-1,2]$$

This is because, with the set and enumeration in question, the largest sum cannot be more than $2$ and the largest difference cannot be less than $-1$. Hence,

$$\bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty} V_i \subseteq [-1,2]$$

Now consider that:

$$[0,1] \subseteq \bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty} V_i$$

To prove this, consider an element $a \in [0,1]$. As the equivalence classes partition $[0,1]$, $a$ must belong to some equivalence class $[v_a]$. As $a \in [v_a]$, $a-v_a \in \mathbb{Q}$. As both $a$ and $v_a$ $\in [0,1]$, this difference cannot be smaller than $-1$ or bigger than $1$. Hence, $a - v_a = e_a \Rightarrow a = v_a+e_a$ for some rational number $\in [-1,1]$. Hence, $a \in \left(V + e_a\right)$ as $\left(V + e_a\right) \subset \bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty} V_i$, $a \in \bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty} V_i$

Therefore, the full inequality of sorts is:

$$[0,1] \subseteq \bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty} V_i \subseteq [-1,2]$$

As $\mu$ is order preserving:

$$\mu\left([0,1]\right) \le \mu\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty} V_i\right)\le \mu\left([-1,2]\right)$$

As $\mu$ is countably additive:

$$1 \le \sum_{i=1}^{\infty}\mu\left(V_i\right)\le 3$$

As $\mu$ is translation invariant, $\forall i \in \mathbb{N}$:

$$\mu\left(V\right) = \mu\left(V + e_i\right)$$

Hence,

$$1 \le \sum_{i=1}^{\infty}\mu\left(V\right)\le 3$$

No $\mu(V)$ satisfies this inequality. If $\mu(V) > 0$ the sum blows to $\infty$, which is greater than 3. For $\mu(V) = 0$, the summation would yield 0 which is greater than 1. Hence, there is no value in $[0,\infty]$ that satisfies the above inequality. That is, $V$ cannot be measured. As $V \subset \mathbb{R}$, this breaks the first intuitive property established for $\mu$. Clearly, any such $\mu$ defined on all of the power set of the reals cannot exist. Some other domain that works well with the intuitive properties of measure must be defined. This leads us to $\sigma$-algebras.

Defining $\sigma$-algebras

$\sigma$-algebras are a special kind of set algebra. A set algebra over some set $S$ is a field-like structure defined to be a family of subsets $F$ such that:

-

$F$ is closed under complementation.

-

$F$ contains the $\emptyset$.

2b. Along with 1. the above imples that $S \in A$

- $F$ is closed under finite union. That is:

$$\forall i \in \lbrace 1,2,3, … n \rbrace A_i \in F \Rightarrow \bigcup_{i=1}^n A_n \in F$$

Proof: $F$ is closed under finite union $\Leftrightarrow$ $F$ is closed under finite intersection.

Consider some sequence of sets $A_i \in F$, $i \in \lbrace 1,2,3, … n \rbrace$.

As $F$ is closed under complements, $A_i^c \in F$.

As $F$ is closed under unions,

$$\bigcup_{i=1}^n A_n \in F$$

Again, as $F$ is closed under complements,

$$\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^n A_n^c\right)^c \in F$$

By De’Morgans law:

$$\left(\bigcup_{i=1}^n A_n^c\right)^c = \bigcap_{i=1}^n A_n$$

Hence,

$$\bigcap_{i=1}^n A_n \in F$$

A $\sigma$-algebra $\Sigma$ over some set $S$ is a set algebra such that condition 3. now states that $\Sigma$ is closed under countable unions. That is, for some infinite enumerable sequence $A_i \in \Sigma$,

$$\bigcup_{i=1}^{\infty}A_i \in \Sigma$$

The proof that this implies closure under countable intersection is the same as above.

Simple examples of $\sigma$-algebras over a set $S$:

-

$\mathcal{P}(S)$ is a $\sigma$-algebra.

-

$\lbrace S,\emptyset\rbrace$ is a $\sigma$-algebra. It is the simplest $\sigma$-algebra.

Clearly, $\sigma$-algebras lend themselves well to intuitive notions of measurability. For some set $S$ and subset $A$, if you know how ‘big’ $A$ is and how ‘big’ $S$ is, you should be able to work out how ‘big’ $A^c$ is. If you know how ‘big’ some sequence of sets is in $S$, you should be able to work out how ‘big’ their union or intersect is.

Generating $\sigma$-algebras from a family of sets

Given a family of sets $F$, $\exists$ a unique smallest $\sigma$-algebra containing $F$.

More specifically this is the intersection of every $\sigma$-algebra that contains $F$. To prove that taking the intersection of every $\sigma$-algebra that contains $F$ is a $\sigma$-algebra and minimal, consider that:

Proof: If $C_i$ is a set of $\sigma$ algebras on $X$, then the intersect $\cap_i C_i$ denoted

$$\bigwedge_iC_i$$

is also a $\sigma$-algebra:

If $e \in C_i \text{ } \forall \text{ } i$, then it is guaranteed that $e^c \in C_i \text{ } \forall \text{ } i$ as all the sets in question are $\sigma$-algebras. Hence,

$$e \in \bigwedge_iC_i \to e^c \in \bigwedge_iC_i$$

That is, the intersect is closed under complement. As all the sets in question are $\sigma$-algebras,

$$\emptyset \in \bigwedge_iC_i \text{ , } X \in \bigwedge_iC_i$$

Consider some enumeration of sets $A_j \in C_i \text{ } \forall \text{ } i,j$. As all the sets in $C_i$ are $\sigma$-algebras,

$$A_j \in \bigwedge_iC_i \forall \text{ } j \to \bigcup_j A_j \in \bigwedge_iC_i$$

That is, the intersect is closed under countable union. Hence the intersect of $\sigma$-algebras is a $\sigma$-algebra.

Proof: If $C_i$ is the set of all $\sigma$-algebras on $X$ containing a family of sets in $X$ called $F$, the intersect is the minimal $\sigma$-algebra containing $F$.

As $F \in P(X)$ and $P(X) \in C_i$, $C_i$ is not empty.

Therefore,

$$F \in \bigwedge_iC_i$$

It has been shown earlier that the intersect of a set of $\sigma$-algebras is a $\sigma$-algebra. Moreover, the intersect is minimal in the sense that, for any $C \in C_i$,

$$\bigwedge_iC_i \subseteq C$$

This minimal $\sigma$-algebra is called the $\sigma$-algebra generated by $F$ and is denoted $\sigma F$